by Kenneth L. Field

If someday they take the radio station away from us, if they close down our newspaper, if they silence us, if they kill all the priests and the bishop too, and you are left alone, a people without priests, each one of you must be God’s microphone, each one of you must be a messenger, a prophet.

Óscar Romero, July 8, 1979

I recently completed a chamber opera entitled, “Romero: God’s Microphone.” This was a four and a half year journey from conception to completion. As it turns out, this period also coincides with a spiritual journey of my own. Rather late in life, I decided to return to my music composition background which started in my teens at Interlochen Arts Academy – a private arts school in northern Michigan – where I graduated from high school. Many years later, shortly after completing a Ph.D. in linguistics from UC Santa Barbara in 1997, I married my wife, Rafaela, who was finishing her Master’s degree in Latin American & Iberian Studies. Two years into our marriage we ended up in the Los Angeles area where I was leading a worship team consisting of drums, acoustic guitar, bass, and vocalists at a small church in Pico Rivera. The roots of the worship music was mostly from the Vineyard Christian Fellowship and a few songs I had written myself. The style ranged from reflective to rock-and-roll. Rafaela was teaching history at two local community colleges (and playing drums for the worship team.)

As my involvement with music increased, I realized deep down inside that there was an unfulfilled longing. I was being drawn back to my classical/art music roots. My hope was to compose music which spoke to both the intellect and the heart and to also bring to light social injustice and prejudice. I craved musical expression that was deeper and more intellectually satisfying and challenging than the praise and worship songs I was leading every Sunday morning. But I was burdened with guilt because I felt that the musical expression I desired to create was too esoteric to make any real difference to those who were suffering.

Around this time my wife and I were given a book that brought some clarity to my confusion: Madeleine L’Engle’s Walking on Water. Her premise was that there was no difference between Christian and non-Christian art. Good art is good art. And what I mean here by art is not just the visual arts, but all art – painting, literature, sculpture, music, etc. For me this new understanding meant that worship and praise music was not on a pedestal or somehow more blessed than any other kind of music or art. This understanding was very weak or almost non-existent in the Protestant tradition that I came from. For me, this insight opened up a new vista for me and allowed me to set aside my guilt. So I applied to California State University in Fullerton with the hope of getting a graduate degree in music composition. Despite not having an undergraduate music degree, I was accepted, and started classes in the fall of 2001.

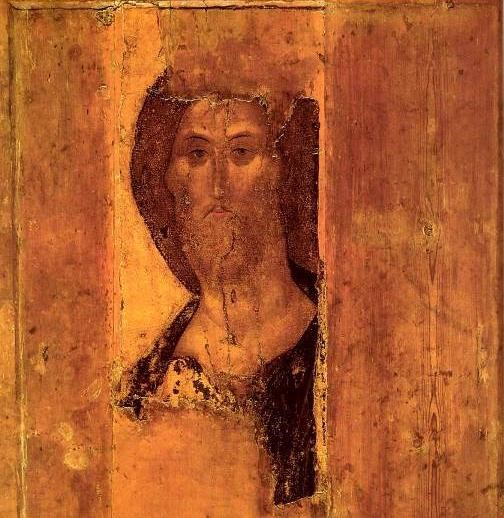

This new understanding of art also led to an in-depth exploration of Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy where the interaction between art and faith is better understood. One of the best examples of where art and faith meet is in the concept of the Eastern Orthodox ikon. An ikon in the Eastern Orthodox understanding is not just a painting of a Jesus or Mary or a saint. An ikon is a window into heaven. One common misunderstanding is that the Eastern Orthodox pray to ikons, but this is not true. Rather, they pray through them. They are not the object of prayer but rather a means to facilitate prayer.

One of the benefits of this investigation into Eastern Orthodoxy and Catholicism was that it allowed me to step into the shoes of the other and see the world from a different spiritual perspective. I discovered that there was a oneness that was the Church, but that over the centuries it had divided into multiple traditions. These in turn grew, matured, and split apart even further over time, resulting in manifold factions, branches, and identities. So that now, individuals have become so rooted in their own cultural/religious traditions that they are unable to see beyond their place of identity and accept the differences of the other. The outcome of all this is that religious traditions and denominations that grew from the same source dismiss each other as not being true to the faith. We are no longer brother and sisters but competitors – even enemies. Rather than finding common ground where we can stand together, we use our belief system and doctrine as a badge to identify what club, branch, or sect we belong to. If our badges don’t match, we are at odds and the result is disharmony – not unity. My spiritual journey has led me to reject the outside pressure to categorize myself. It has challenged me to accept the other and seek common ground.

In the spring of 2003, I graduated with an M.A. in music composition. Shortly after this Rafaela was accepted in the Ph.D. program in the history department at UC Santa Barbara, so we moved back in the fall of 2004. With my music degree behind me I struggled (and still do) to find the right expression for it. Then in the spring of 2010 I came across a call for chamber opera scores. If your work was selected, it would be performed. The idea was to send a ten minute excerpt fully scored and the complete libretto – which is the sung text and storyline for the opera. I had six weeks to finish this enormous task. What would be my subject? What would the opera be about? Most operas revolve around heroes and heroines, lovers and cheaters, sexual liaisons and murder. Not quite the subject matter I was interested in. But the one idea that interested me was that the hero or heroine almost always dies in the end. Then I remembered a movie that I was introduced to while Rafaela and I were still dating: Romero starring Raul Julia in the lead role. I had never forgotten how the movie had impacted me. At the time, I was more interested in China than Latin America. (Rafaela soon changed that.) But the story of the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero had struck a chord in me. With my wife working on her Ph.D. with an emphasis in Latin American history, I had the perfect go-to person to help me with my research on Óscar Romero. I read about his background, I read his homilies, his weekly radio addresses, his diary, and the details surrounding the last few weeks of his life. I found out he liked to listen to Marimba music to relax, so I made the marimba one of the central instruments in the opera. I read about a life-changing encounter that a nun named Eva had with Romero and made this into one of the scenes of the opera. I was able (somehow) to finish the libretto (in its initial form) and the opening ten minutes of the opera and submitted it to the competition. After a few weeks of anxious waiting I found out that my work had not been selected. I inquired why my work had been rejected and the answer I got – much to my surprise – was that it was too violent. They were looking for something with a more pleasant, lighter topic – or perhaps less challenging. Romero went on the back-burner.

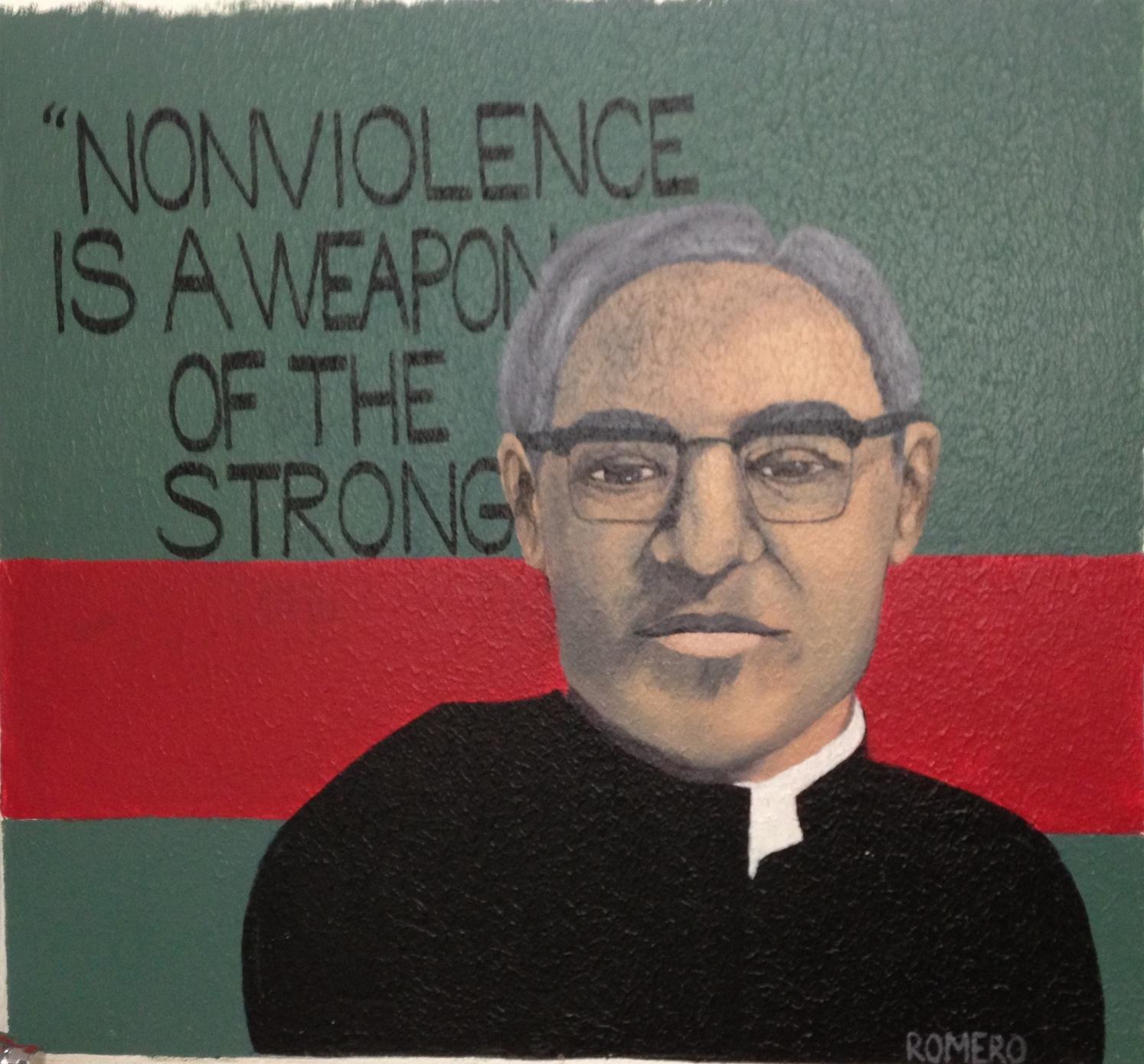

The following year Rafaela accepted a faculty position in the History Department at Whitworth University. In the fall of 2013, our family had the opportunity to go to the Costa Rica Center (an extension campus, now closed, for Whitworth students) where Rafaela would be teaching a full load. I was teaching one class but I needed something more to occupy my time. So I brought my Romero score and music notation software thinking I might have some time to work on it. The decision proved to be fortuitous. On the first full day I walked into the men’s public restroom at the Costa Rica Center and there on the wall was a large painting of Óscar Romero. There he was – staring right at me. That painting in the men’s bathroom was like an ikon for me – a window of transcendence. So I started looking at my score from three years before.

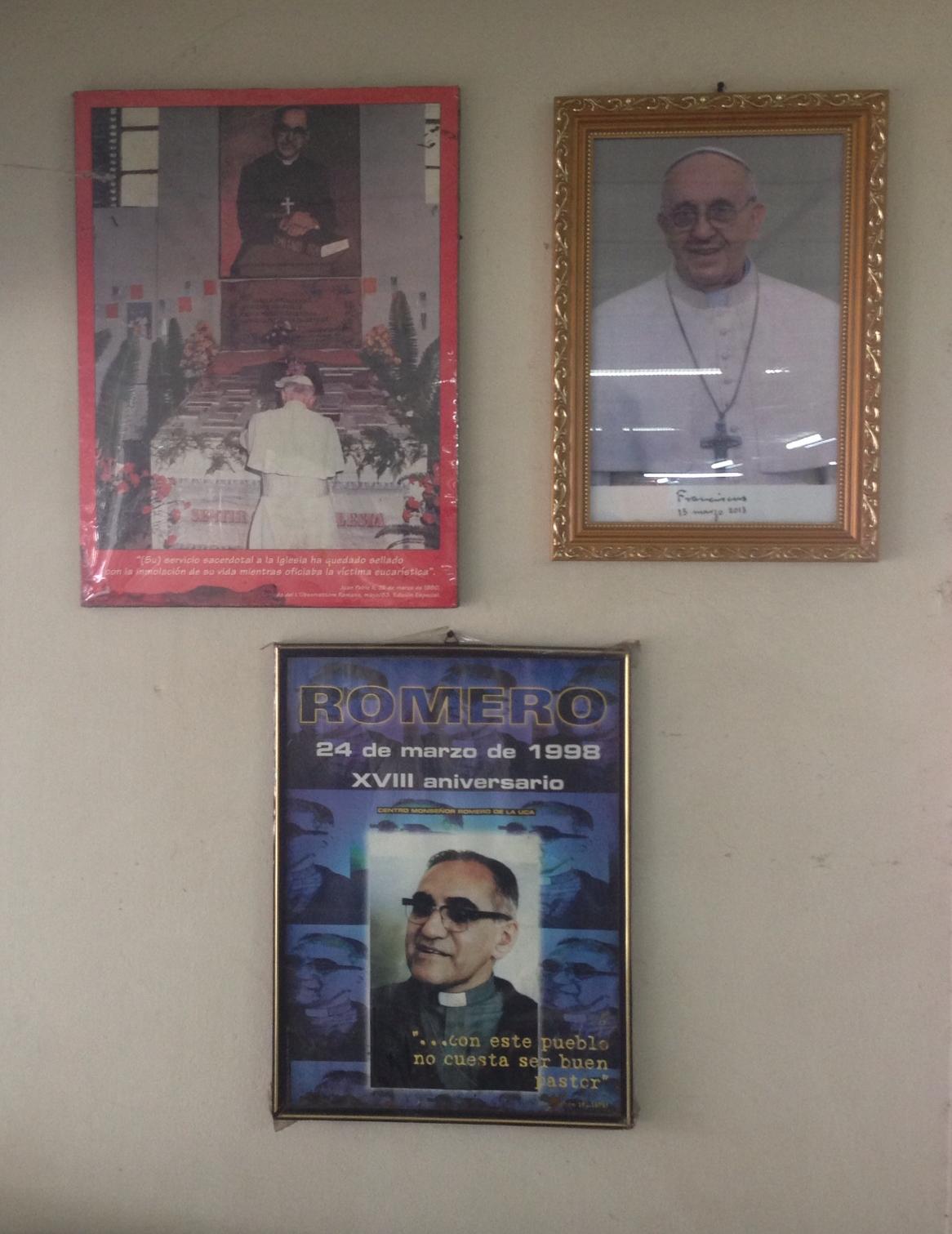

A few weeks into our family’s stay at the Costa Rica Center, all the Whitworth students, assistants, and faculty participated in a week-long trip to Nicaragua. We all hopped on a public bus and rode the eight hours from San José, Costa Rica to Managua, Nicaragua. On Sunday morning we visited a base community church – a Catholic Church that was formed during the Nicaraguan revolution in the 1970s. We were all struck by the fact that there were only a few older men in attendance – the congregation consisted mostly of older women and their families. We surmised that most of the men had died in the revolution. The church welcomed us with open arms and even invited us to take part in the Eucharist – even though most of us were not Catholic. There was no priest. A woman led the service and administered communion (which is practically unheard of in the Catholic Church at large). Although my Spanish wasn’t that good, I was deeply touched. After the service ended we were mulling around the small church. On the back wall were three framed pictures: one of Pope John Paul II kneeling before a shrine to Óscar Romero, one of Pope Francis, and a poster of Óscar Romero commemorating the 18th anniversary of his death. March 24th of this year marked the 36th anniversary of the day he was assassinated while celebrating mass.

As I looked at this display in the little Nicaraguan church, it was at that moment I realized Romero was already treated as a saint in Central America. There are even songs sung in the church service about him. All this had been happening years before his recent recognition as a martyr by the Vatican. On May 23, 2015, 35 years after his assassination, Óscar Romero was beatified in San Salvador, the first step towards being recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.

About eight weeks after our trip to Nicaragua we all went on another side trip – this time a week-long trip to Cuba. While we were in the San Salvador airport, waiting for our connection, I was stunned when I noticed a large painted mural in one of the airport concourses: it was of Óscar Romero – in the very city where he had been gunned down by a government-sponsored assassin. This mural was for me another ikon. And it was a sign that the example of Romero was there to stay in El Salvador. Death could not keep him silent. And in a way it fulfilled his words:

I have frequently been threatened with death, I do not believe in death without resurrection. If they kill me, I shall arise in the Salvadoran people. I say so without boasting, with the greatest humility.

Óscar Romero, From an interview, March, 1980

Between our trips to Nicaragua and Cuba, I arranged for a room where I could write privately. I started working daily on the opera. I threw out most of what I had written in 2010 and started over. The initial attempt was framed in a modernistic musical idiom – very dissonant and much harder to grasp conceptually due to the lack of a key center and few memorable melodies. This avant-garde musical style is usually not as well received by the general public. So I decided that I would stay closer to the tenets of minimalism – known for its repetition and more pleasing harmonic style. I wanted something that would quickly draw people into the story rather than alienate them before the story even began. The libretto, the lyrics or storyIine of the opera, had been completed in 2010. With only a few minor changes and some needed editing, I finalized the libretto and moved on to the music. With the private room, I was able to spend one to two hours a day composing mainly on weekdays. This continued for a number of weeks. I have probably never written so much music in such a short period of time – almost 40 minutes worth. I was able to finish nearly two-thirds of the opera while I was in Costa Rica.

Upon our return to Spokane in January of 2014 and our re-entry into the American lifestyle, it took a number of weeks before I got into the habit of writing again. And with some valuable input and editing from Paul Raymond and Brent Edstrom – both professors in the Music Department at Whitworth – I was able to put together a final draft of the opera in October 2014.

With the recent news of Óscar Romero’s beatification I feel an urgency to share his story. When he was appointed Archbishop of El Salvador in 1977, he did so at a turbulent and complicated time in Salvadoran history. He was considered by the government and the Catholic Church hierarchy to be a safe choice. Trained in Rome, it was assumed that he would not make waves. But under Romero’s watch the political situation evolved in such a way that a strong state, backed by a traditional oligarchy and a strong military, became increasingly repressive towards a population that demanded freedom for workers to unionize and demand better wages, access to healthcare, and freedom of the press. After Romero’s death the situation worsened and escalated into a civil war that didn’t end until 1992, claiming tens of thousands of lives.

Not long after Romero was appointed, it became clear that he was not going to be the Archbishop the government and Catholic hierarchy wanted. Only a month into Romero’s tenure, Father Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit priest with whom Romero had become close friends, and two others who were riding along with him were ambushed by paramilitary forces. The three were shot and killed while returning in a Jeep from Aguilares where Father Grande spent most of his time ministering. The death of Father Grande changed Romero. He took the time to personally meet with his parishioners and to listen to their stories and concerns. He traveled extensively throughout El Salvador and heard their stories about oppression, murder by government allied forces, and all the men and women who had disappeared and never returned.

Rather than side with the oppressor, Romero sided with the oppressed. He was simply following the example of Jesus. And this did not go over well with those in high places. Over the course of the next three years, five more priests were assassinated by forces siding with the government and countless civilians as well. Every Sunday in his weekly radio address Romero would preach the gospel and call for peace. And everyone had radios and everyone listened.

Then on March 23, 1980, a Sunday, in his homily at the Sacred Heart Basilica in San Salvador (the largest church in El Salvador) he asked each soldier to follow his conscience and not shoot to kill his fellow Salvadorans, even if he was ordered to do so.

In the name of God, in the name of our tormented people who have suffered so much and whose laments cry out to heaven, I beseech you, I beg you, I order you in the name of God, stop the repression!

Óscar Romero, From his homily of March 23, 1980

Archbishop Romero had to have known that he was likely signing his death wish by asking the soldiers to disobey the orders of their commanding officers. The next evening, March 24, he was celebrating Mass at a small church in San Salvador called the Divina Providencia Chapel. That night he read the gospel passage which was from the church calendar for that week.

The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified. I tell you the truth, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds. The man who loves his life will lose it, while the man who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life. Whoever serves me must follow me; and where I am, my servant also will be. My Father will honor the one who serves me.

John 12: 23-26

As he was raising the bread and wine to heaven and calling down God’s blessing down upon them, a single shot was fired from outside the open doors of the church. It struck Romero square in the forehead. The bread and wine fell, the body and blood of Archbishop Oscar Romero was spilled on the floor of the church. The seed died. The nuns wailed. The assassin walked away and was never found.

Retelling the story of Romero in opera is for me one way of being God’s microphone. His story is just one of many that needs to be heard. The opera actually opens with Romero’s assassination and then flashes back to a few weeks before his death. In addition to Romero (whose role is sung by a tenor), the list of characters includes an apparition of Father Rutilio Grande (a bass), a Carmelite nun named Eva (a soprano), and the assassin himself (a baritone). Many of the words the Romero speaks are words that were actually spoken or written by Romero himself.

The small ensemble that accompanies the singers includes a string quartet, a contrabass, a piano, two marimbas, a percussionist, and a brass trio. There is also a chorus of four nuns and four paramilitary soldiers. The chamber opera lasts just over an hour. I am currently pursuing avenues to get the opera performed in whole, but it is more likely at this point that smaller sections or arrangements will be performed first.

Whether you consider yourself religious or not, the example of Romero cannot be ignored. He knew what was required of him and he did not flinch. Romero followed the example of Jesus. He stood up for the poor, the oppressed, the rejected, and the ostracized. He called on those who remained after his passing to be “God’s microphone” – an allusion to his weekly radio address. 36 years later, we are still called to be God’s microphone. We are called to speak the truth about injustice and prejudice, even though it may hurt us. May we all have the courage to follow the example of Romero.

Kenneth L. Field graduated in 2003 with a Master’s in music composition from California State University Fullerton where he studied under Pamela A. Madsen. Previously he graduated in 1997 with a Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of California at Santa Barbara. For many of his works, Field’s linguistics background informs his music compositions. His 2002 work fifty seven one for sixteen vocalists is built upon waves of sound created from the different phonemes of the English language. The work was recorded in 2006 by The Kiev Chamber Choir and released on CD in 2008. In 2004, his work The Beatitudes, for tape, was presented as part of the Electrolune Festival in Lunel, France. This work’s sound source is a recording of the Beatitudes from the gospel of Matthew spoken in six different languages. Small snippets were manipulated in various ways to create this ten minute sound canvas. A work consisting mainly of guided improvisation, Baptism – a musical rite of passage – for Ean, was performed by ThingNY on Feb. 25 at SPAM v. 2.0 at the LaGuardia Performing Arts Center in Long Island City, New York. A prerecorded version of his 2011 work, Saint Brendan and the Lyrist, for soprano and tape was presented March 5, 2011 at the CSUF New Music Festival in Fullerton, California. The sound source for the tape portion of this work were manipulated recordings of his son Brendan’s toys. In October of 2014, Field completed a chamber opera entitled Romero: God’s Microphone, which covers the event’s surrounding the last few weeks of Archbishop Óscar Romero’s life up until his assassination on March 24, 1980. Las Calles de La Habana (The Streets of Havana), for flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and piano was completed in May of 2015. This work was predominantly inspired by his weeklong trip to Havana in November of 2013. It recounts the feeling of traveling the many streets of Havana and meeting and listening to the Cuban musicians in the Plaza de Armas. In December he completed a miniature for soprano and cello entitled, Unwind. His next work will be a song cycle for piano and soprano based on texts by Barbara Kingsolver, Thomas Merton, and Ernesto Cardenal.

You can find recordings of some of these works at: kennethlfield.bandcamp.com.

Photos 2-5 courtesy of the author. Photo 2: An early ikon of Jesus: Andrei Rublev’s Christ the Pantocrator, 1410