Joshua Robbins

As we enter Advent’s home stretch, I’ve found myself wishing the season’s anticipation would feel…well, more sublime. But, then again, I wonder if Advent should feel sublime. Is this a season of sublimity?

As we enter Advent’s home stretch, I’ve found myself wishing the season’s anticipation would feel…well, more sublime. But, then again, I wonder if Advent should feel sublime. Is this a season of sublimity?

And what do we mean by “sublime,” anyway? Is grandma’s Christmas ham sublime? Is the passing of the flame during the Christmas Eve candlelight service sublime? How about that high note in “O Holy Night”? If anything is sublime, surely that high G is, no?

Well, it seems the first rule of the sublime is similar to the first rule of Fight Club: you do not talk about the sublime. Or, well, maybe it’s more like: you cannot talk about the sublime.

Well, it seems the first rule of the sublime is similar to the first rule of Fight Club: you do not talk about the sublime. Or, well, maybe it’s more like: you cannot talk about the sublime.

Third-century rhetorician Longinus described an encounter with the sublime as an experience in which the soul “takes a proud flight, and is filled with joy and vaunting.” This experience of uplift is “produced by greatness of soul, imitation, or imagery,” and is an experience that cannot be contained or expressed by language.

For centuries, philosophers, Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant among them, have written extensive definitions of the sublime in an attempt to understand and explicate that which feels like momentary contact with the ineffable. Even in today’s disintegrating world of commodity fetishism, hierarchical mumbo-jumbo, etc., postmodern philosophers like Slavoj Žižek continue to unpack this sublime encounter that leaves us without words, that transports and elevates our souls. And that’s been the centuries-long problem with talking about the sublime: to talk about it in language is to diminish the totality of it.

Despite the fact that it’s written in words and so it is automatically disqualified as a legit description, I find Emily Dickinson’s maxim about poetry immensely useful as a way of relating to the sublime. With apologies to the Belle of Amherst whose poems can, I think, lead us right up to the precipice of the sublime, here are her words with one significant adjustment in italics: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is sublime. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

So, I’d like to know what you think. Can Advent be sublime in the fashion of Longinus and Emily Dickinson?

So, I’d like to know what you think. Can Advent be sublime in the fashion of Longinus and Emily Dickinson?

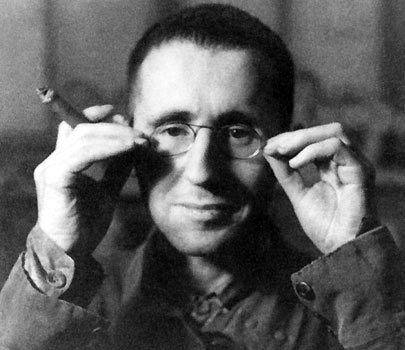

This month, I’ve found one handy response to my question in a poem by Bertolt Brecht, the great twentieth century Marxist playwright, director, theorist, and poet, who may be best known popularly today (with Kurt Weill) for The Threepenny Opera and influencing musical artists like Jim Morrison, Tom Waits, and P.J. Harvey, among many others. Here’s the poem:

Mary

The night when she first gave birth

Had been cold. But in later years

She quite forgot

The frost in the dingy beams and the smoking stove

And the spasms of the afterbirth towards morning.

But above all she forgot the bitter shame

Common among the poor

Of having no privacy.

That was the main reason

Why in later years it became a holiday for all

To take part in.

The shepherds’ coarse chatter fell silent.

Later they turned into the Kings of the story.

The wind, which was very cold

Turned into the singing of angels.

Of the hole in the roof that let in the frost nothing remained

But the star that peeped through it.

All this was due to the vision of her son, who was easy

Fond of singing

Surrounded himself with poor folk

And was in the habit of mixing with kings

And of seeing a star above his head at night-time.

Imagistically, it’s a fairly straightforward Christmas poem: a starry night, a stable, angels, shepherds. Been there, done that. But even with its normative Yuletide menagerie, Brecht’s “Mary” ain’t your typical crèche. Brecht’s poem challenges us to critically engage the history and legacy of the Christmas story and break down what we see in both the poem and, subsequently, in our individual relationships to Advent.

In Brecht’s poem, the reader is forced to see the birth of Christ as an actual birth. When was the last time you encountered a manger scene with accompanying placenta? And whereas a run-of-the-mill Christmas poem might compel us to squeeze out an approximation of catharsis from its lines or might manipulate our emotions toward that all-too-inevitable impact of a Christmas poem’s narrative, this Mary has forgotten how it all really went down, forgotten about the cold, the shame, the poverty, the exposure. All recollection of how it was in Bethlehem has been replaced over time with the stuff of holiday legend leaving the reader to be challenged to recognize their own complicity in the historical revisionism.

Marxist critic Fredric Jameson suggests we can locate the sublime in Brecht when we see “the frame and focus of [Brecht’s] representation suddenly enlarge to include the world itself, and Being.” In “Mary,” we are confronted with a revised, revolutionary history of the nativity. Consequently, Brecht’s poem affords us opportunity to enlarge the frame of the manger scene and Mary’s experience in order to recognize the areas in our own lives in which we’ve lost our connection to how-things-really-happened. And in this respect, one might argue that Brecht’s poem does offer an encounter with the sublime during the Christmas season.

The Christmas story is not one that regularly lops off the top of my head. The truth is I may be so jaded that I’m incapable of experiencing the true sublimity of this season. But because of Brecht’s poem, I recognize how my passive acceptance of a cynical attitude toward the “holiday experience” makes me complicit in enabling the relentless, life-sucking Christmas-revision power of malls, shiny paper, and commercial jingles marketing cheap crap. In other words, I need to get back to basics, to the cold night, “dingy beams,” “smoking stove,” and especially to the “bitter shame” of being the lowly.

This season, I may not feel how I would if my soul were taking flight, but I certainly feel like Advent’s delivered a bare-knuckled closed fist to the jaw of my soul, and I’m okay with that. I’ll take that punch. And if I go down for the count, I’ll be okay with that, too. At the very least, I’ll have something to talk about.

Merry Christmas.

Citations: