Jeremiah Webster

– noun ( /ˌænəɡˈnɒrɨsɨs/; Ancient Greek: ἀναγνώρισις) the moment in a play or other work when a character makes a critical discovery.

“What is the single greatest line of poetry?” the doctor asked.

“What is the single greatest line of poetry?” the doctor asked.

I was on butcher paper with hypertension and a persistent eye twitch. Stabbing chest pains on the bus had prompted me to check into the university health clinic as soon as I arrived on campus. The doctor had done the stethoscope tongue depressor otoscope routine and was now sitting behind his desk. He recited a poem from Rilke that he had translated from the original German and repeated the question. Not your average MD.

Graduate school had been a steady dialysis of Foucault regimens and Post-Structural diatribes, progressive vaccines laced with hegemonic antibodies. I was happy to oblige, I excelled even, but the enterprise was soulless: Nietzschean fodder with lots of vapid “discourse” about “community.” My body was in Bastille revolt. “I’m going to die,” I had told my wife, hand on forehead like one of Edward Gorey’s lost souls. My propensity for melodrama never wavered.

“Do you ask all your patients this?” I asked the doctor.

“Only graduate students in English,” he replied.

I rambled some opaque answer that included Yeats, the Psalms, Dickinson, Dante, Homer, most of Paradise Lost, and King Lear entire. Nonsense, obligatory name dropping, but I hadn’t anticipated this physician’s literary Q&A either. The pain was acutely worrisome, and I couldn’t imagine (rather ironically) what poetry had to do with chest pain, so I changed the subject and asked if he had any recommendations, prescriptions, terra firma pills.

“Nothing,” he said. “That isn’t your problem.” He then asked if I liked the Goldberg Variations and if I could think of a performance that matched Gould’s in ’55. “You’re not like the others,” he said as he wrote down the names of three books to read by year’s end: Lives of the Poets, Doctor Zhivago, and the collected works of W.H. Auden. “You are a Christian,” the doctor said without a question mark.

“Yes,” I replied, startled. We were moving into psychic Coast to Coast AM territory.

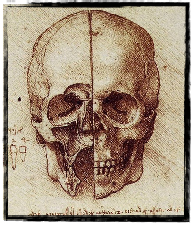

“I spent the entire morning assuring undergraduate students that they hadn’t contracted STDs from various strangers they fucked. Give me remedy, they say. People expect medicine to solve everything.” He paused, looked beyond me to the wall, and continued, “We all die, all of us. That is why poetry matters.” There was a long silence. Room for vespers. A lifetime of church attendance and scholastic endeavor hadn’t prepared me for any of this. I was Tiresias at Delphi, Electra graveside, Peter before Jesus.

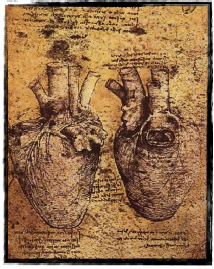

“I am the Resurrection and the Life,” the doctor incanted. “This is the greatest line of poetry.” Perched as I was, like Eliot’s patient revived, made his declaration inhabit the wyrd, as though my entire pursuit of a PhD had culminated in this moment. And the more I thought about it, the more compelling his answer became. “What I do is easy,” he continued, “caring for bodies isn’t complicated. Nourishment, exercise, sleep, it’s self explanatory. Biology is all nuts and bolts. The soul is another matter entirely. You need poetry for that.”

“I am the Resurrection and the Life,” the doctor incanted. “This is the greatest line of poetry.” Perched as I was, like Eliot’s patient revived, made his declaration inhabit the wyrd, as though my entire pursuit of a PhD had culminated in this moment. And the more I thought about it, the more compelling his answer became. “What I do is easy,” he continued, “caring for bodies isn’t complicated. Nourishment, exercise, sleep, it’s self explanatory. Biology is all nuts and bolts. The soul is another matter entirely. You need poetry for that.”

We were an hour into a fifteen minute appointment. I was late for class. Moments later I would be involved in a rather sophistic group discussion on spermatic economies and gendered spheres. I thanked him and said I needed to go. “One more thing,” he said. “I do not share your faith, but you must love your enemies. Love them, or you will never be well.”

* * * *

The doctor’s words would prove to be my heart’s corrective. Poems like “The More Loving One” and passages from Bach’s aria were committed to memory. The severe pain I had endured for months vanished. I realized how lethargic, bitter I had become, body divorced from spirit, how modern, with my delusional compartments of self. There was no follow up, making the doctor’s exam assume a kind of mythic intensity with each passing year. It was the best instruction I would receive during my tenure in graduate school. It was the absence of pretense. It was anagnorisis, lifted from the page of an Aeschylus play.

Wir dürfen dich nicht eigenmächtig malen / Rainer Maria Rilke

We must not portray you in king’s robes,

you drifting mist that brought forth the morning.

Once again from the old paintboxes

we take the same gold for scepter and crown

that has disguised you through the ages.

Piously we produce our images of you

till they stand around you like a thousand walls.

And when our hearts would simply open,

our fervent hands hide you.

Trans. by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy

6 Responses

Great post. You have a poetically raw and beautiful way of using words to paint pictures. Every scene has layers of depth with seeds for further thinking and learning. Thank you for sharing this powerful truth.

I’m starting a week of poetry study for my college class. Take a guess what the first assignment will be! Great writing!

One of the best posts I’ve read in a long time. Thank you.

Looking forward for the next one.

supreme.

Very powerful, Jeremiah. Thank you.