Kaitlin Schmidt

“Hi! Have you heard of Rock & Sling?”

This is the inane question I started with as I stood at our booth, a sweaty and tired traveling saleswoman. I was posing. I’m a writer; what do I know about making money? During my initial shifts, I gave a practical spiel about Rock & Sling niche to any victim who made eye contact. Oh, there is the head nod of thinly veiled boredom and drifting eyes. There is the inching away, there are the vapid agreements. At first I told them too much all at once, desperate for them to validate my position behind the table by buying something. Despite my enthusiasm, sales were low.

I lost steam. I am relational at heart, so all of my efficient sales techniques turned into conversations about something else. One lady with an accent stopped by and asked if we accept submissions for bilingual work. I gave a noncommittal answer to hide my ignorance and probed the topic to find out more. She was from Greece and wrote her work in two languages. I was fascinated. She told me that, though she is in America, her heart is still “over there.” I responded with sympathy. It must be hard to be so far away from home. She asked which free back-issue she should take, and I described a couple of them, ending with the one I personally liked best. She gave me a big smile and took that one, saying, “We’ll go with your favorite.” I smiled, pleased, and she departed.

A man with a stroller came by and shook hands with me. He introduced himself as Kevin Goodan, a skilled poet whom we had published in the most recent issue. His son was sleeping, for which Kevin seemed grateful, so we spoke in low voices. I was surprised at how kind he was. I was relieved that such a good writer might also be a good person. I saw him again later with his wife. This time their son was wide awake and squirming endlessly. Thom came by and we stood around our booth talking, blocking any potential customers and having a great time.

Once while I was standing in the aisle in front of the booth, a girl was walking past aimlessly. Acting on impulse, I caught her eye and greeted her. I asked her if she had heard of us as an excuse to talk to her. When I explained what Rock & Sling was about, she seemed shocked and pleased. She told me she has a really strong faith that feels out of place at her public university. I, too, was surprised, and we talked about faith and the tension she lives in. She was ecstatic to find a literary journal committed to conversations born of that tension. She took some swag and bought a copy of our new issue without a second thought. (My only sales were unintentional.)

She then said with confidence that she wanted me to participate in something. Curious, I watched as she pulled a thin, rectangular black box from her bag. She told me how a group of people used to draw authors’ blood samples in order to preserve their essence. I felt the bottom of my stomach drop out. Here, I had been thinking how cool this girl was and how I would like to get to know her better, and now she pulls out a sinister container full of author blood? She was probably part of some adoring writer cult and thought AWP was the best place to practice her outdated and slightly vampiric passion. I felt myself involuntarily inch away.

She laughed and explained that her and her collaborators liked the idea, but instead of collecting blood, they wanted to collect words. She undid the clasp and opened the box. No test tubes. I was relieved. Instead, there were orderly rows of microscope slides. She handed me one, along with a permanent marker, and requested a word. I thought about it for a minute, wrote my word, and handed it back. She had me sign my name on a corresponding sheet of paper, and we parted on good terms.

As she walked away, I wondered how long that word would be preserved. Money is one thing; it comes and it goes. On the other hand, words might be eternal.

Meredith Friesen

The panels were formed by, to a poor measly undergrad, the greatest professionals in their field. I didn’t always agree with what they said or how they approached any given topic, but I quickly learned that I was at the bottom of the food chain and that any qualms I had probably would not hold. Once, a fellow youth spoke up during a panel and, quite frankly, sounded ignorant and inexperienced. The panel answered his question very nicely, and then they asked him to come and talk afterwards, the topic not being fitting for the entire group.

On a panel on teaching “setting the scene”, the professor speaking made a joke at the expense of undergrad writing, noting how any story written will probably take place at a dorm room or a local eatery, it would be about relationships or parties. The entire room laughed, knowing what he meant. While I agreed with their statements and gave a small chuckle, having read several terrible pieces myself, I was slightly affronted. I never wrote a story about libraries or a fight with my roommate. Why was I being lumped with the beginning writers? What I realized was the professor never meant to offend me; I was not the target audience. The other professors, writers, or MFA students were.

I am a senior at a small school in a small city. I am about to graduate and conquer the world or something to that extent. I do not want to be like the cocky student from Michigan. I hope to enter the official adult world with a bit more dignity and humility than that. I liked being at the bottom. I liked looking at the thousands and thousands of people who share my interests, and are way smarter than me, and seeing that I can grow to become something like them. I am a young writer, but it’s nice to know that I have a lot ahead of me.

Derek Strausbaugh

I went to a panel called “Magic and the Intellect” where Lucy Corin, Rikki Ducornet, Kate Bernheimer, Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum, and Anna Joy Springer talked about pushing boundaries in literature, and using magic as a tool to push those boundaries. Lucy Corin opened up the panel reading an unpublished piece, with a title that I cannot recall. The premise of the piece was that a woman had tried to commit suicide by taking pharmaceuticals, and her father was trying to keep her awake by telling her dead baby jokes. It was interesting how the crowd reacted at the beginning of the piece. There was uncomfortable laughing at first, then less laughter, then mostly cringing. Before the end of the piece an audience member stood up and yelled at Corin, interrupting her and telling her that the story was disgusting. I agree, the dead baby jokes were disgusting. This visceral reaction just proved that what Corin had written was well-crafted, and the other attendees and panelists leapt to Corin’s defense and said as much. I do not like dead baby jokes. I can take one or two before I try and change the subject. Corin’s piece made me squirm, and feel dark and dirty. At the end of the piece, I felt real grief for what the father was going through. Corin seemed to be wrestling with grief, and how it may not be pretty, and can stir up ugly emotions and reactions. Grief and loss is rich territory to explore, and Corin did so in a very real, very raw, and very uncomfortable way, and I have to commend her for that. As she finished the piece, my feeling of distress from the jokes dissolved into a defeated sadness for the father.

This is what writing can do. This panel was fantastic in showing how the envelope can be pushed. Writing as a medium can put all of these uncomfortable and hard to describe feelings into a story that acts on your gut. Writing should challenge the audience to feel wonder, or hurt, or disgust. I met a number of very interesting people, and saw very talented Christian writers tackling similarly difficult issues, particularly at the Wordfarm, Rock & Sling, and Ruminate reading and reception. One piece told the story of a garden that was torn up because of a woman who could only believe the worst of her neighbor. A poem that was read discusses the strangeness of marriage, and how special that is. As a writer, there is an obligation to tell a truth that others can engage with. AWP provided a place for these pieces to inform one another, and challenge writers to engage with these same questions on their own. I left A.W.P. knowing that if you wrestle with these questions, there is a greater community doing the same thing in their writing. I feel challenged to tell a story where someone will yell at me, or even better, write their own story in response.

Karina Basso

Over the last year, I began seriously practicing literary translation, which, funny enough, came about from a random conversation during last year’s conference in Boston. However, it seemed to me that 2014 Seattle, my third year at AWP, was the year of translation. There was hardly a time slot that did not offer a panel or reading focused on the subject. The panels, readings, and book fair were a valuable resource for practical knowledge, advice, and opportunities to network or submit works of translation. More importantly, this year’s conference acted as a sounding board for my current and forthcoming translation projects as I spoke with novice and experienced practitioners.

One element that stood out to me in conversations in and outside of panels was the question of faithfulness. At what point does attempting to produce a translation faithful to the original work stand at odds with art and creativity? Is it more faithful to capture the spirit and beauty of language used by author rather than producing an accurate, yet stilted copy of the original in the target language? Some panelists proposed more liberty and creativity in translation, while others challenged translators to understand and respect the linguistic implications of the original text while stretching and morphing the capabilities of the target language.

For me, AWP 2014 offered a place of exploration and growth in my studies and future vocation that was not as easily accessible to me during my undergraduate studies. It’s not surprising to me that there are not many MFA programs that offer translation. Within the American literary community, translation is seen is as the awkward stepchild let in based on loose familial bonds. To some writers and poets, translation may seem derivative and uncreative. But I agree with panelist and international translator Elizabeth Harris’s assessment that “Translation is pure writing.” That is, it is writing freed from the normal conventions of writing. With translating fiction, a translator does not have to worry about creating a plot and characters, but must understand the author’s work so well that the word choices, syntax, and minute phrasings in the new language read as if they had been written in that language. With poetry, the lines and diction should read with the same care as if the translator were the poet who originally produced and slaved over every single phrase and punctuation. It was these types of conversations and others during the week at AWP that have affirmed my belief in the value and need for translation within the literary community.

Dana Stull

Well, I’m back from the most English major-oriented adventure I’ve ever experienced. I survived, thrived even. I got thirty free literary journals. I got fifteen stickers to put on my Nalgene. I got thirty pounds of buttons. I don’t know what to do with the buttons. But to summarize my experience, here are five things I observed.

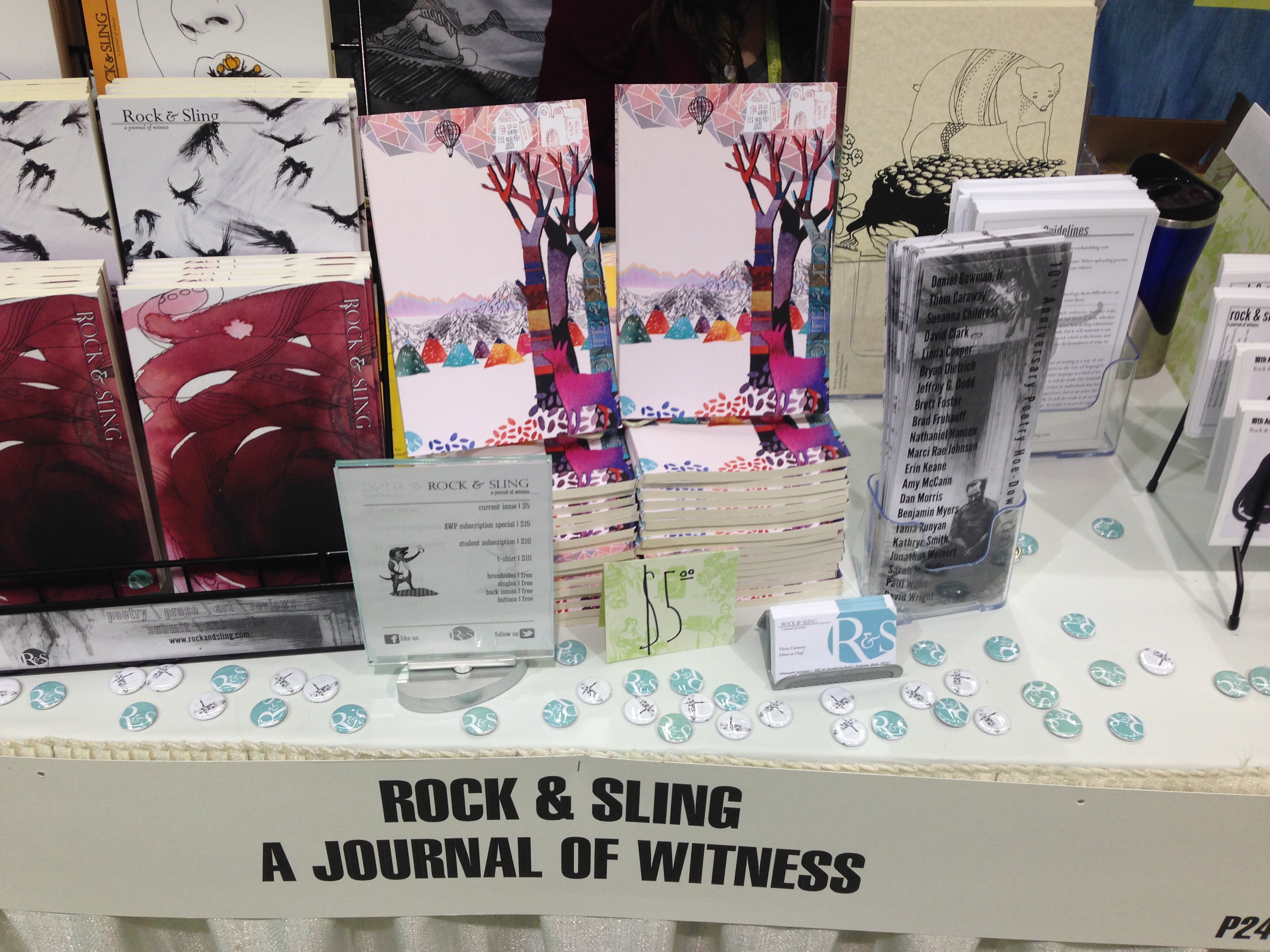

1. The smaller literary journals had the neatest tables, and were the most willing to talk about their journal. Cave Wall shared their journal, and asked about Rock & Sling. Willow Springs gave away many back issues for free, and were eager to talk about what they were excited about in their current issue. Several of the other tables I visited ended up coming to visit our table later on. There was a sense of respect and appreciation between the smaller journals, instead of a competitiveness that I was expecting.

2. Cover art makes a significant difference in the world of lit journals. So many people stopped at the Rock & Sling table because the covers caught their eye, and then stayed and took time to read some of the work. I know I rushed past tables that had unappealing covers, though I knew that was no indication of the quality of work. The cover really is the first impression, and it is highly influential.

3. Some tables really thought outside of the individually-wrapped-chocolate-box Burnside Review handed out matches. Versal handed out insanely strange black licorice salt candies. Beloit gave away shortbread cookies and tangerines. Sugar House Review handed out saltwater taffy. Another table was handing out shots of whiskey. It worked. I was drawn in by the interesting provisions, and stayed for the top-notch journals.

4. Turns out, the writers that Rock & Sling publish are in fact real people. Several of the writers published in the latest issue came by to see their work in print, and introduce themselves. It was cool to put a face to a name, and to share how excited we were about their pieces.

5. On the emotional spectrum of people attending the conference, I noticed most people either looked desperately indifferent to the entire environment, or were giddy, expressive, and walking around with full tote bags and new literary t-shirts. I much preferred the spazzed enthusiasts, as I was one of them.

Emily Mangum

This was my first year attending AWP. I thoroughly enjoyed the readings and panels I went to, and I loved wandering around the bookfair to collect such books as Drawn to Marvel, Minor Arcana Press’s new anthology of superhero-inspired poetry. But the most memorable part of the conference was probably the various conversations I had with my fellow Rock & Sling staff. These ranged from in topic from the problematic characterization of Pa Kent’s character in the new Man of Steel movie to why we undergrads love our professors so much and how those relationships can change after graduation.

By far the best conversation occurred on Saturday evening, over dinner at The Veggie Grill. Karina Basso and Meredith Friesen had sat down in a crowded Starbucks that morning next to a woman named Marybeth who had given them instructions for getting to this place. So our group of seven women trooped down the few streets from the Convention Center and proceeded to discuss boys over drinks, dinner, and sweet potato fries (it was all surprisingly good considering how much of a vegetarian I am decidedly not). The conversation went something like this:

Alyssa Olds to Kaitlin Schmidt: “What, you haven’t heard that story already?”

(Cue chorus of groans from the rest of us as Kaitlin shakes her head.)

Alyssa: “So this guy. I was on the escalator on my way to a panel when the old guy next to me starts talking to me. Just a casual conversation. When I got off the escalator I forgot about it. Then later, this same guy comes up to me and says, ‘It’s you!’ Eventually he mentioned something from our earlier conversation, so I remembered who he was. So we talked – he introduced himself, invited me to some reading his program was having. Which, I guess isn’t that abnormal. I told him about our reading. When we were finishing our conversation he said, ‘Well, I have to go. Could I get your number? Maybe hit you up later?’ And I was like, ‘Um…no,’ and then I just walked away.

“When I got back to the Rock & Sling table I told Caroline, ‘Oh my gosh, this really old guy just totally hit on me and asked me for my number and I don’t think he knows that I’m twelve!’ And Caroline was like, ‘Is that how you see yourself?’”

This story, which most of us had already heard once or twice, spawned a whole conversation about strange interactions we’d all had with guys. Caitlin Wheeler talked about an awkward date in excess of four hours long that she’d had with a guy in our university coffee shop. Karina Basso told us the story of how she came to have a Canadian boyfriend. I talked about the good-friend-turned-criminal I’d had a crush on all through junior high and high school (until the criminal bit happened, of course…). As we separated for the night, some of us to a hostel and some of us back to the Convention Center to wait for the Sharon Olds and Jane Hirshfield reading, we all agreed we were glad it had been just us girls for that dinner.