by Amanda C. R. Clark

The house is quiet; parents are sleeping. You create a tent under the sheets; you switch on the flashlight. You fumble the book open, acutely conscious of its crinkling pages. And then, you read. Just you and the book and the delightfully stealthy act of being awake, late into the night.

There is a joy, too, in reading as adults, in the summer, at leisure. It is a luxury we rarely allow ourselves, sometimes only on planes or on vacation. But do you remember that stealthy act of reading, under the bed-tent, late at night, in the dark?

Sometimes our world goes dark, and we need reading more than ever. Sometimes reading is our deliverance.

China’s infamous Cultural Revolution, from 1967-1977, is often called, in China, the “ten-year catastrophe.” Books (and the libraries that housed them) were deemed part of the “four olds:” old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits. Books were destroyed, often by fire, in order to “free” and “save” the country from an oppressive, feudal past. It was a misguided effort to wipe the slate clean and start anew.

Those who had formerly lived a life of the mind—scholars, writers, students, artists—felt the deprivation of books and libraries in an especially profound and painful way. Some sought, and obtained, illegal books to read, doing so at the risk of various punishments including beatings, public “struggle sessions,” detention, limitation or denial of food rations, unemployment, and forced relocation into harsh and remote labor camps. Rather than being deterred, many intellectuals became obsessed with secretly obtaining contraband books, both foreign works in translation as well as classic Chinese Confucian texts. The literature—and the physical, defiant act of reading—had a profound effect on those who dared to read, revelations that are expressed repeatedly in the memoirs and autobiographies of those who lived through this era. During this time, when the illiterate were praised and the literati were sent to the countryside to be “re-educated,” and when forms of communication were state-controlled, watched, and scrutinized, reading was a defiant gesture of independent selfhood. Although most intellectuals eventually were able to return to the cities, they were forever haunted by the shadow of a violently ruptured past.

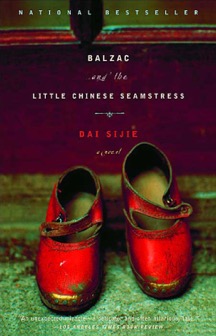

If there is one book you schlep to the beach disguised between mindless paperbacks, perhaps it will be the short but captivating novel by Dai Sijie, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress. Dai draws us into the world of the Cultural Revolution following the path of a pair of lovers and their love for the secret reading of forbidden Western books. At times an uncomfortable and disappointing book, the themes of power, fear, passion, education, and longing, stay with you long after the last page is read. While drawing you close to questions about knowledge and the power of print, it will take you far away, not only to the China of the mid-twentieth century, but to rural China during a time of tumult.

If there is one book you schlep to the beach disguised between mindless paperbacks, perhaps it will be the short but captivating novel by Dai Sijie, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress. Dai draws us into the world of the Cultural Revolution following the path of a pair of lovers and their love for the secret reading of forbidden Western books. At times an uncomfortable and disappointing book, the themes of power, fear, passion, education, and longing, stay with you long after the last page is read. While drawing you close to questions about knowledge and the power of print, it will take you far away, not only to the China of the mid-twentieth century, but to rural China during a time of tumult.

George Santayana quipped that those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it. I suspect there is much that those of us living in the contemporary United States can learn from China’s twentieth-century past. Is monetary wealth a source of liberation? Or is it knowledge, literacy, and education? Will we again, as adults, return to our late night, flashlight-lit, under-cover reading habits? Will the thrill of reading return to embolden and mature us as it did once did before?

Recommended reading:

Dai Sijie, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress: A Novel (2002).

Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (2003).

Kang Zhengguo and Susan Wilf, Confessions: An Innocent Life in Communist China (2008).

Wu-Ming-Shih and Pu Ning, Red in Tooth and Claw: Twenty-Six Years in Communist Chinese Prisons (1994).

Amanda C. R. Clark is Library Director at Whitworth University. She has published in areas of architecture, biography, book arts, and the significance of books. Clark holds a PhD in library and information sciences from the University of Alabama.

One Response

I grew up in the ’50s and early ’60s and I remember the admonition to eat all my food because people were starving in China. And that was the extent of what anyone really knew about the Cultural Revolution. And indeed they were starving, dying by the thousands. But as this post points out, they were also starving for the written word, which, on the surface, seems incidental to the real hardships. As i think about how immersed I can get into a good book, I see how feeding the mind in this way feels like roses releasing their bouquet, cool nectar on the tongue, or water to a wilted flower. As we’ve seen in history of other times, such as WWII Germany and in the old USSR, censorship does not work. The thirsty will seek the water no matter the consequences. We must never forget this as we go into a book store and survey the many books, just ripe for the reading.