Jeremiah Webster

In 1858, Heinrich Schliemann (retired at thirty-six after success as a military contractor) set out to discover the walls of Troy that he had read about in Homer’s Iliad. This would be like saying, “I will find the Black Gate of Mordor,” after reading Tolkien’s TheLord of the Rings. Critical consensus during Schliemann’s day assumed the historicity of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey to be on par with Ovid’s Metamorphosisor the Tooth Fairy. But Schliemann, unmoved by scientific dogma, packed his bags and headed for modern day Turkey. He read passages from the Iliad that described Troy’s fortifications and surrounding landscape. He postulated where the Achaeans had moored their black ships. When he came to locations that mirrored the wine-dark specificity of Homer’s song, he started digging. Implausibly, Schliemann found an ancient civilization now believed to be the actual site of Ilium, nested between the Aegean and Black seas. It garnered Schliemann international (i.e. notorious) fame and secured his status as the “Father of Modern Archeology.”

In 1858, Heinrich Schliemann (retired at thirty-six after success as a military contractor) set out to discover the walls of Troy that he had read about in Homer’s Iliad. This would be like saying, “I will find the Black Gate of Mordor,” after reading Tolkien’s TheLord of the Rings. Critical consensus during Schliemann’s day assumed the historicity of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey to be on par with Ovid’s Metamorphosisor the Tooth Fairy. But Schliemann, unmoved by scientific dogma, packed his bags and headed for modern day Turkey. He read passages from the Iliad that described Troy’s fortifications and surrounding landscape. He postulated where the Achaeans had moored their black ships. When he came to locations that mirrored the wine-dark specificity of Homer’s song, he started digging. Implausibly, Schliemann found an ancient civilization now believed to be the actual site of Ilium, nested between the Aegean and Black seas. It garnered Schliemann international (i.e. notorious) fame and secured his status as the “Father of Modern Archeology.”

Notorious, you see, because Schliemann’s methods were hardly scrupulous. He failed to notice that he had found not one, but seven versions of Troy, one on top of another: a kind of anthropological layer cake. He unearthed masks, urns, weapons, and helmets, believing everything he found must necessarily be attributed to the Trojan War. Schliemann cast elaborate names upon these objects as they were retrieved slipshod from the soil. Sophia, his wife, wore the jewels he found. His techniques (which included dynamite) elicit the gag reflex among contemporary archeologists. It was Troy beneath a colonial jackhammer, shock and awe treasure hunting, a Troy whose sole purpose was to be discovered by an affluent recreational class. His legacy suggests that however progressive we may feel, human nature has a knack for pillage.

* * * *

I thought of Heinrich a few months ago as I toured Seattle’s Underground. Like Troy, the Emerald City was built on top of a previous version of itself after the Great Fire of 1889. The tour was geared around the disposable souvenirs one usually finds at Disneyland or local Star Trek conventions, but I was resolved to transcend the sing-song monologue of bad jokes and inevitable exit through the gift shop. I would be as wide-eyed as the young German of ’58, minus the explosives and archeological theft. There was plenty to admire beneath the streets housing Pike Place Market, Jeff Bezos, and the Cannabis Dispensary, plenty to leave one humbled by how transitory the human drama truly is.

The guide led us down a staircase and into a room that was once a storefront looking out over what is now Yesler Way. A Pre-Prohibition bar stood like Nosferatu’s coffin in the center of the room. Baroque patterned wallpaper curled along the seams of the entrance. Two windows were now empty frames spanning the height of the northern wall. Aside from an occasional hiss from the city’s waterworks, the place was a silent tomb. Our guide played up the fact that this part of town was haunted. I was inclined to agree. Beneath the forte clamor of Seattle’s modern streets, there was an underground haunted by silence, by serenity, by the last witch to face tribunal in the loudest of all eras.

* * * *

George Steiner once remarked that modernity was, “a systematic suppression of silence.” That our society has embraced cacophony so readily (I’m looking at you smartphones), that individuals become alarmed by even a moment’s pause from their digital bombardiers, confirms the fears of Morris Berman when he writes, “…the use of the phone…enables us to dominate public space, to violate it, in effect, and thus demonstrate to others (now rendered invisible) that there is absolutely nothing they can do about it.” While the early twentieth century was a landscape of failed communal utopias (militant nationalism, eugenics, and the myth of Marx), we now worship the progress of iEgo. Narcissus masquerades as a social network.

Touring Seattle’s Underground forced me to come to terms with how displaced I feel in this age of sound and fury. The silence I encountered in those subterranean rooms made me want to set up shop, roll out the sleeping bag, and listen until the stillness consumed me. I used to reminisce about the past, for the good old days of plague and cholera, Visigoth and Vandal. My nostalgia was gilded, biased towards what my students call “old school,” that is, life before 1985. But the problem with this paradigm is self-evident. Like a forgetful Lotus Eater, I had cultivated a selective memory, a narrative minus what Aristotle called hamartia (a.k.a. “the fatal flaw”). As obnoxious as 2012 might be, every age is horror show. The cries for death in the Colosseum were equally immoral.

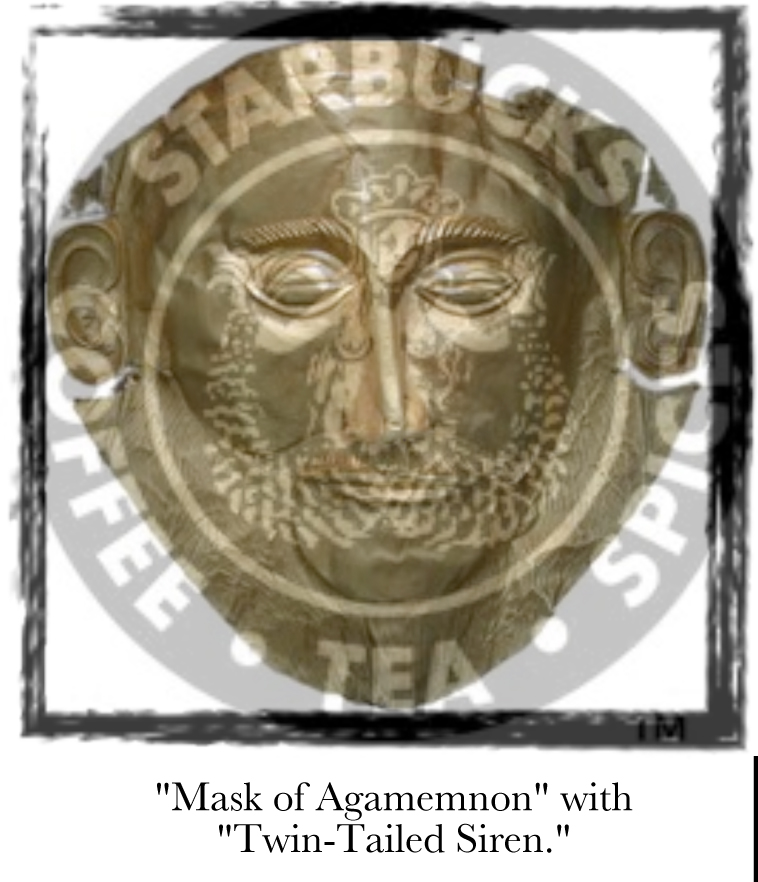

Seeing that bar with its floral wallpaper, the abandoned gear shaft rusted into obsolescence, recast my vision of history. Rather than gaze back for consolation (my standard default), I began to look forward, to a time when Seattle replaces Ilium as the antiquated city, and Starbuck’s siren eclipses Agamemnon’s mask. This exercise was actually quite redemptive. Recognizing the denouement of places and objects made them more meaningful, not less. The telos of the human narrative became less about attaining some kind of utopia here on earth, and more about the extravagance of where we find ourselves. As a Christian, my sense of grace and providence was reinforced. The music of all times and places mattered.

One day every iPhone in America will lose its charge and luster. Centuries from now, the hollow fuselage of a Boeing Dreamliner will wait beneath the prairie for a contemporary Schliemann to find. And at the end of history, all who came before that last generation will appear barbarous and backward, Vlad the Impaler and Steve Jobs alike. The 2048×1536 Retina Display will fade like all the others. Despite the claims of strict empiricism, evolution, progress, Kubrick’s Star Child, a sci-fi “Singularity” was never the point. “For us there is only the trying,” T.S. Eliot writes, “the rest is not our business.”

“What has been is what will be,

and what has been done is what

will be done;

there is nothing new under

the sun.”

Ecclesiastes 1:9

7 Responses

Beautiful piece. Thank you for sharing.

Well done, as usual! There’s so much to unpack in what you’ve written.

Thoughtful observations. Wonder what Schliemann would do with the “clang, clang, rattle, bing bang” of our world today.

Good software are able to do many things to help you begin creative writing. If you have plans to monetize your website, your best course of action can be to invest with your own hosting and URL name. http://tinyurl.com/qzmtyn5

My family members every time say that I am wasting my time here at net, except I know I am getting familiarity everyday by reading

thes good content.