People often tell me in hushed tones that they delight in book sniffing. These confessions are wrapped in happy, faux-guilt-laden shrugs of pleasure. There’s something magical in that almond and vanilla odor that wafts from books,[1] with pages sometimes yellow-edged, finger-smudged, marred by the occasional coffee or wine ring, a store-branded bookmark, a price label peeling off, a flower or ticket stub tucked inside. A teardrop wrinkles a page—was it joy, or sorrow, or both? In summer, when the days stretch long, we too stretch out with books in our hands, to read and sniff, perhaps to nap. We digest books in a more leisurely way. The lighter the read, the faster we turn the pages. But there is nothing hurried about summer reading; it is nourishing, not rushed, as we prolong the tangible experience.

For many, new popular fiction is retrieved from the public library. As we know them today, public libraries appeared first in the nineteenth century, where collections could be used freely and exuberantly by the public. Demand was met by (or driven by) production ability; in 1814 the London Times was pulling up to 250 sheets an hour, up from the former 100 sheets pulled manually in preceding years.[2] Rising affluence allowed for more frequent recreational book buying and reading. Voracious readers consumed unprecedented amounts of leisure reading, seen in sales of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which sold copies in the hundreds of thousands.[3] We in the 21st century have inherited this insatiable appetite.

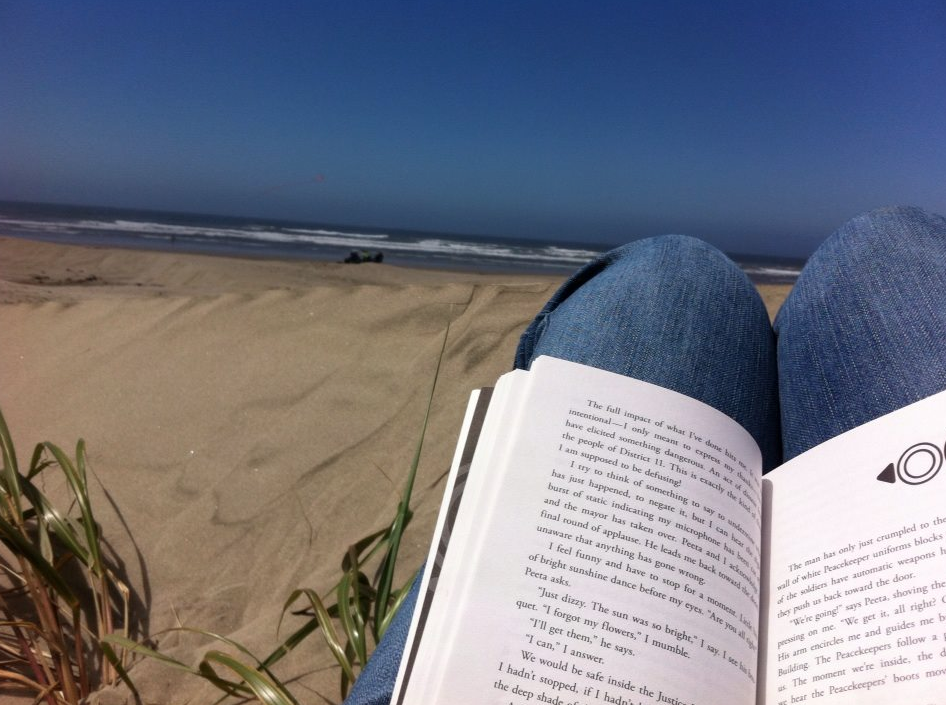

Lazy beach reading is a personal activity, allowing our brains to connect in ways quite dissimilar from any other activity; for something so apparently passive, it is remarkably dynamic.[4] Curled up, stretched out, perched, cuddled, lounging, we experience these novels and non-fiction trifles at close range, both physically close and psychologically near the characters and author. We can’t put them down, we soak them up and the hours tick by; but no matter, we’ve traversed the globe, travelled through time. We were someone else. It is a process of sensory stirrings, a re-awakening from our quotidian realities at work or school. The book is “assimilated into the reader’s reservoir of personal experiences.”[5] It’s a Velveteen Rabbit experience during which we bring characters to life while they in turn make us more real, more deeply feeling individuals, adding to our reservoir of experience. Our pulse slows and our empathy grows. Empathy softens our boundaries, giving us the “ability to resonate with the feelings of another while maintaining an awareness of the differences between self and other.”[6]

And isn’t this at the heart of our summer reading? When we traipse off to the beach with our blanket, hunting for a weathered Adirondack, we have a book in our tote, a book that will both whisk us away into the “other” while focusing us even more precisely on ourselves, in the chair, feeling the breeze, sipping the umbrella-ed drink.

George Hagman describes this empathy as “a special, transcendent form of union, a bond of beauty.”[7] For those moments we are transcendent and the beauty is in the book itself, the rustle of pages, that soft odor of vanilla. Author of the popular book The Time Traveler’s Wife (2004), Audrey Niffenegger believes that books—like her tragic hero—transcend time and space: “To make a book is to address people you’ve never met, some of them not born yet.”[8]

The author of the novel—popular or elevated—has created for us, the readers, a portal to other worlds. We are transported and transformed. As C. S. Lewis said, we do this so we “know we are not alone.” And for this summer pleasure, we are granted longer days, with earlier sunrises and later sunsets, so that we might indulge our desires to read, to sniff, to dream.

Amanda C. R. Clark is Library Director and Assistant Professor of Art History at Whitworth University. She has published in the areas of contemporary artists’ books, architectural history, and library as place. Clark holds a Ph.D. in library and information sciences from the University of Alabama.

[1] Henry Fountain, “Digging Into the Science Of That Old-Book Smell,” New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast), New York, N.Y, 17 November 2009: D.3.

[2] Warren Chappell and Robert Bringhurst, A Short History of the Printed Word, 2nd edition (Vancouver, BC: Hartley and Marks Publishers, 2000), 193-195

[3] Michael Winship, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin: History of the Book in the 19th-Century United States,” paper presented at Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the Web of Culture Conference, Hartford, CT, June 2007.

[4] “Why Reading Matters,” BBC Four video, 1 hour 5 minutes, 16 February 2009 < http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00hk7w3>.

[5] Eileen Wallace, ed., Masters: Book Arts – Major Works by Leading Artists (New York:Lark Crafts, An Imprint of Sterling Publishing, 2011), 6.

[6] Catherine Hyland Moon, Studio Art Therapy: Cultivating the Artist Identity in the Art Therapist (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2002), 49.

[7] George Hagman, The Artist’s Mind: A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Creativity, Modern Art, and Modern Artists (New York: Routledge, 2010), 115.

[8] Audrey Niffenegger, “What Does it Mean to Make a Book?” in Krystyna Wasserman, ed. The Book as Art: Artists’ Books from the National Museum of Women in the Arts (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), 13.